Day 8

Is it better to risk saying the wrong thing than to say nothing in the face of injustice? I don’t know what the right answer to that question is for me, a white cis woman who reaps the benefits of white privilege and supremacy. I was a mess before the release of each and every one of these projects. As in sleepless nights, upset stomach, the usual anxiety culprits. Because with every series I have risked saying the exact wrong thing.

In my first post I talked about how my thinking has evolved since my first Stations of the Cross for Haiti and the regrets I have about that initial attempt. It was an outpouring of my heart, made in a mad dash during Spring Break. When I created the two series that came after it, I had better insight into not just the artwork, but myself. Yet, when I look back now at The Stations of the Cross: The Struggle for LGBTQ+ Equality I have many of the same uneasy feelings about the project as I do about the Haiti series.

All of these projects capture a moment in time. A moment in my own personal time. I can’t neatly separate myself from the work as it reflects my own passions, interests, and scholarship. As I evolve, so too does my work. And they also capture a moment in historical time. As our societal discourse evolves so, too, does the language I use in the prayers I write and the artists statements that I craft. This is both a strength and weakness of the Stations of the Cross projects, but I mostly see it as a weakness. When the Stations of the Cross for LGBTQ+ Equality came out, I used only the acronym LGBT. As language around gender and sexual identity became more expansive, I updated the title. I think it probably ought to be updated again.

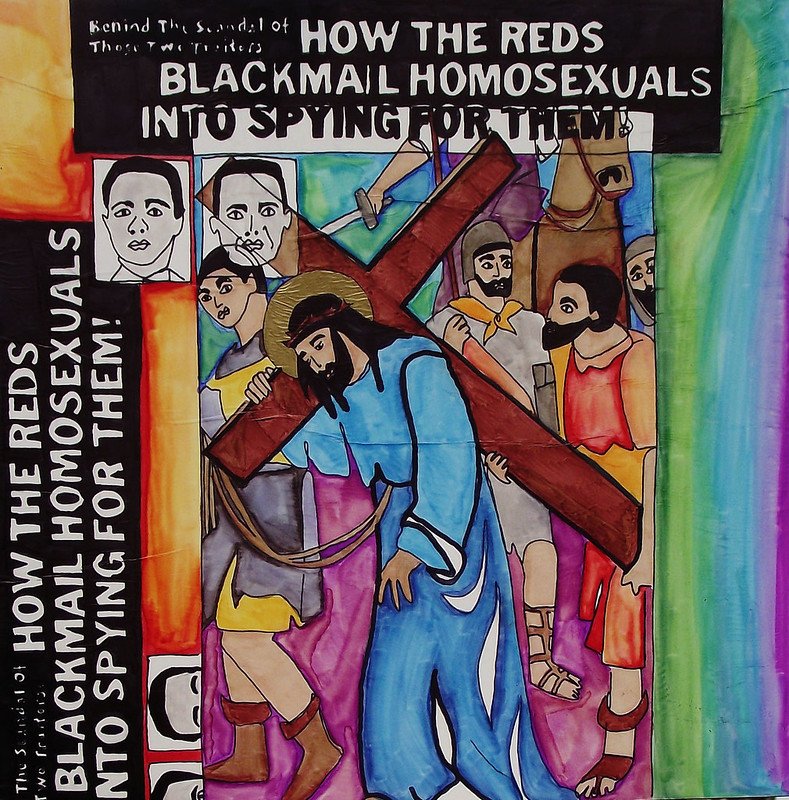

Station 5: Simon of Cyrene helps Jesus carry the cross

1950: 190 individuals in the U.S. are dismissed from government employment for their sexual orientation, commencing the Lavender Scare. The fear and persecution of homosexuals in the 1950s paralleled the anti-communist scare campaigns of McCarthyism.

There are a lot of layers to the LGBTQ+ series in particular. It is a chronological history, meaning that there is an evolution of language documented in the artworks that makes it all the more jarring.

It feels like a weakness to me - how time-bound these projects can be - because I am someone that always wants to be right the first time. Maybe you can relate. I want to be absolutely right about every little thing, down to the very nitty gritty, right off the bat. Even though I know that it’s only through the process of making and creating and getting it fantastically and spectacularly wrong that I’m able to be better. To be a more faithful interpreter of Scripture. This is where I see the strength of the time-bound nature of so much of my Stations of the Cross work - it gives me an opportunity over and over and over again to say I was wrong. To live with artwork for more than a decade (as I have with the Stations) and with each of those passing years, to see how outdated language and imagery becomes, it means that I have an opportunity as a pastor and as a liturgical artist to model what it means as a Christian and, yes, as a white cis person to say, “I’m sorry, I got this wrong. I’ll do better.” And that is something that I say and commit to with every one of these projects, knowing full well that there are things I’ll get wrong anyway.

I want to end this post with one of my very favorite reflections on art-making and the creative process. It’s something the legendary choreographer Martha Graham said in conversation with another legendary choreographer, Agnes de Mille. The conversation was recounted by de Mille in her memoirs where she said it was the most powerful thing ever said to her. She and Graham were in a diner, talking over sodas. Here is how she tells it:

I confessed that I had a burning desire to be excellent, but no faith that I could be.

Martha said to me, very quietly: “There is a vitality, a life force, an energy, a quickening that is translated through you into action, and because there is only one of you in all of time, this expression is unique. And if you block it, it will never exist through any other medium and it will be lost. The world will not have it. It is not your business to determine how good it is nor how valuable nor how it compares with other expressions. It is your business to keep it yours clearly and directly, to keep the channel open. You do not even have to believe in yourself or your work. You have to keep yourself open and aware to the urges that motivate you. Keep the channel open. As for you, Agnes, you have so far used about one-third of your talent.”

“But,” I said, “when I see my work I take for granted what other people value in it. I see only its ineptitude, inorganic flaws, and crudities. I am not pleased or satisfied.”

“No artist is pleased.”

“But then there is no satisfaction?”

“No satisfaction whatever at any time,” she cried out passionately. “There is only a queer divine dissatisfaction, a blessed unrest that keeps us marching and makes us more alive than the others.”

I’ve always loved that turn of phrase, those words - a queer divine dissatisfaction - they capture so much of what I feel about my own work and my own life. Let’s keep marching together, friends!