Day 20

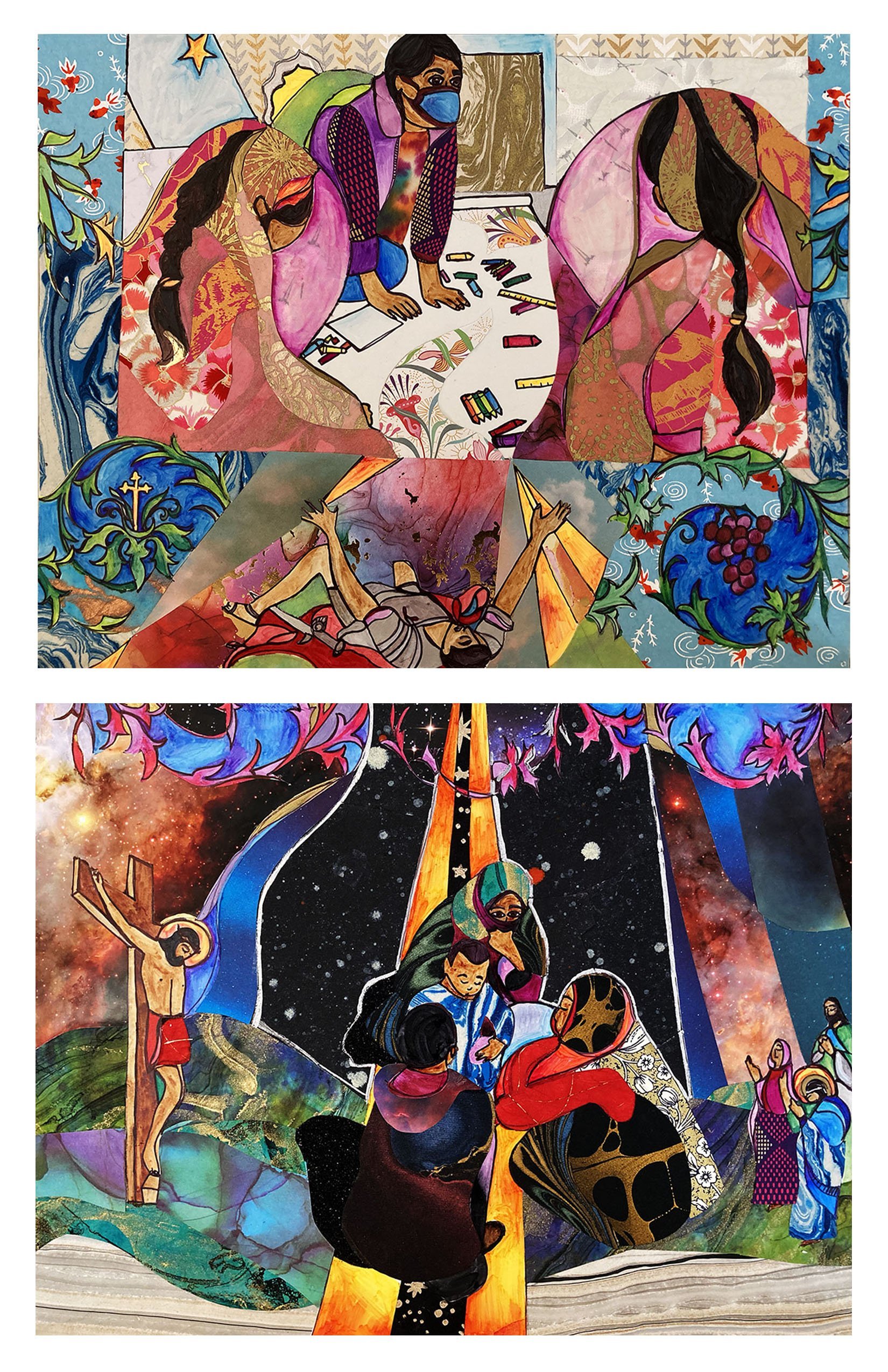

As I have with previous projects that I’ve discussed here, I’m going to start my exploration of Stations of the Cross: Mental Illness by sharing the artist statement that I crafted to go along with it. This series included the publication of a devotional book by the Church Health Center in Memphis, TN and I will be sharing a few updated chapters in the coming posts.

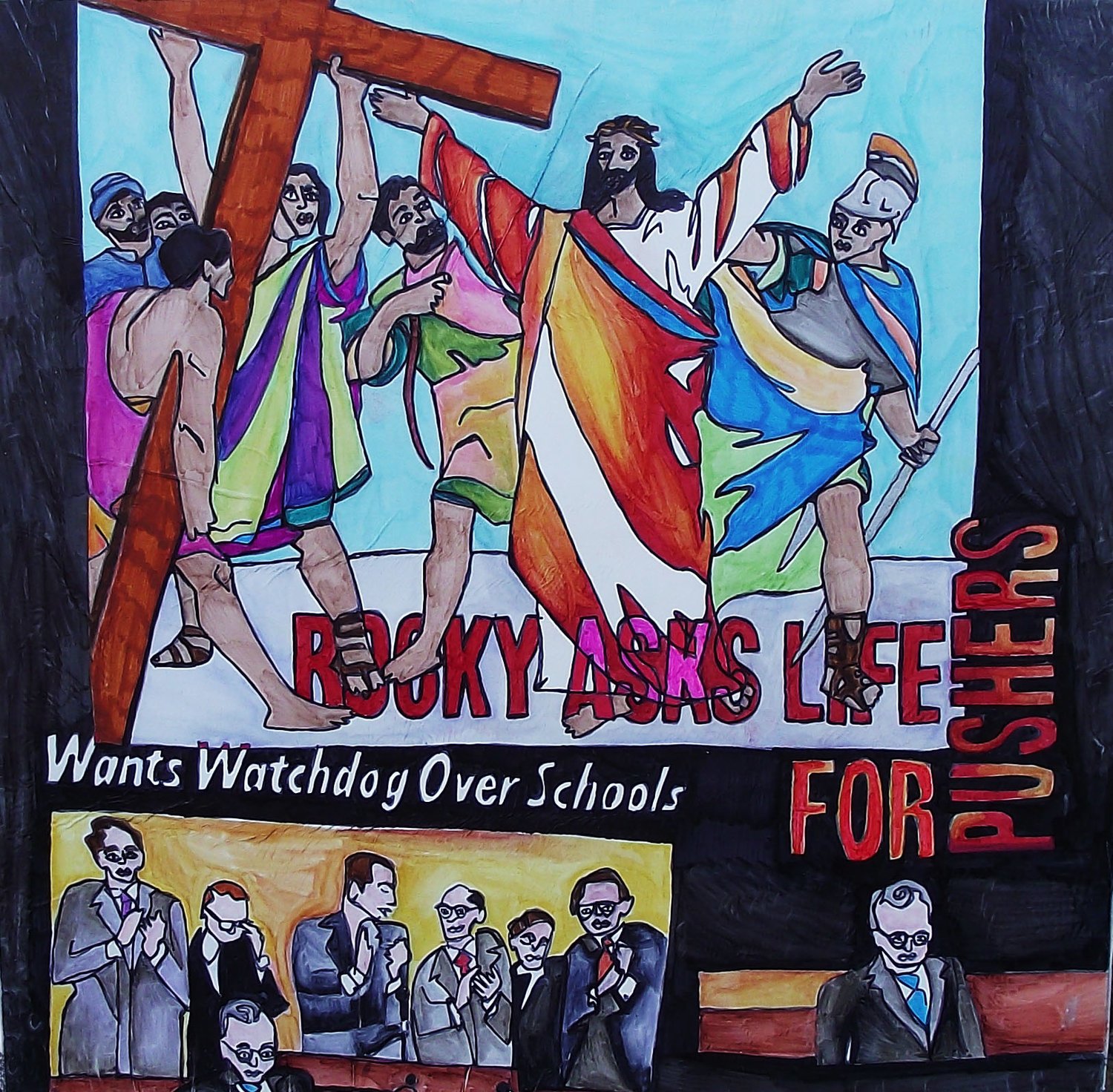

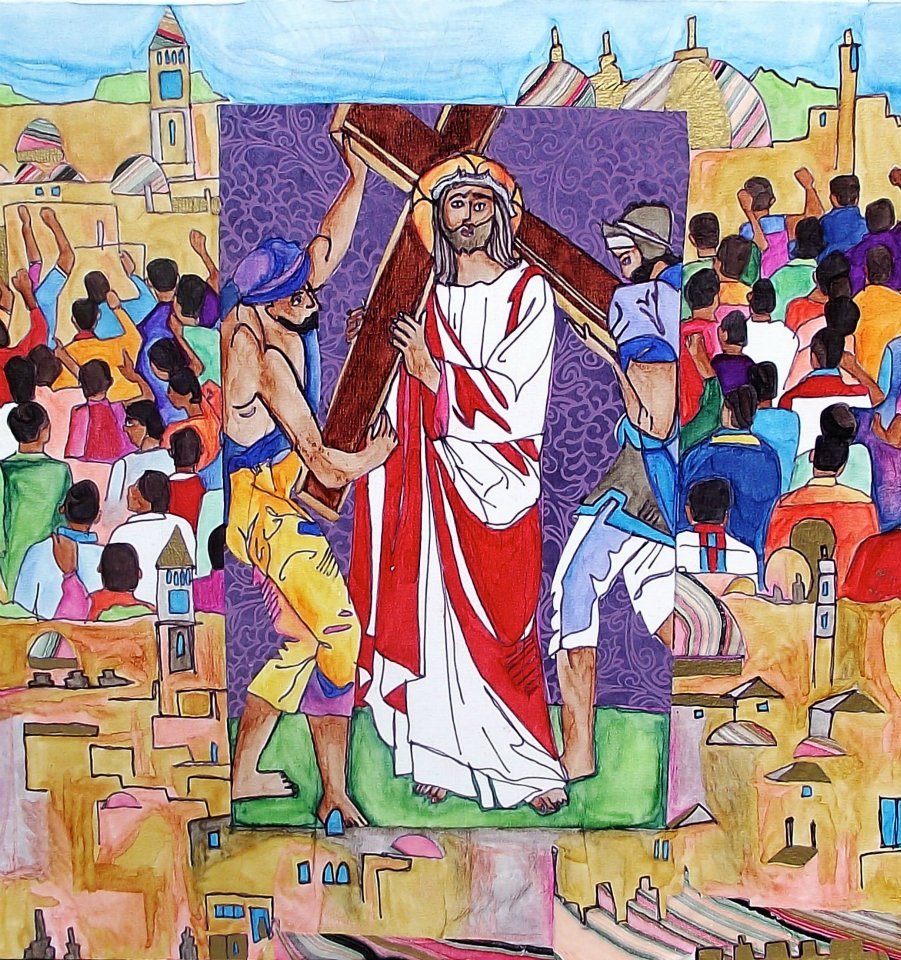

Pilate Condemns Jesus to Death: The beginnings of mania, the beginnings of depression

The hallucinogenic mania that the poet Robert Lowell described once as “a magical orange grove in a nightmare” is where we find Jesus at the beginning of this story. Mania, in its beginning, can feel like a special invitation into a brighter, blazing alternate reality. Always, though, there is a darkness lurking, a toll that must eventually be paid for the sleepless nights and grandiose mornings.

Stations of the Cross: Mental Illness is a deeply personal project. After years of misdiagnoses, medication side effects worse than the symptoms they were meant to treat, and the patronizing disdain of health care providers, I was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. It has been more than a decade since my diagnosis. and most days I'm overwhelmed by the sheer force of color in my life. Friends often comment on the bold colors present in my work, even in seemingly gloomy subject material. Because at the age of 25, with the help of talk therapy and mood stabilizers, it was like the color was switched back on. I began to experience the world in a profoundly new way.

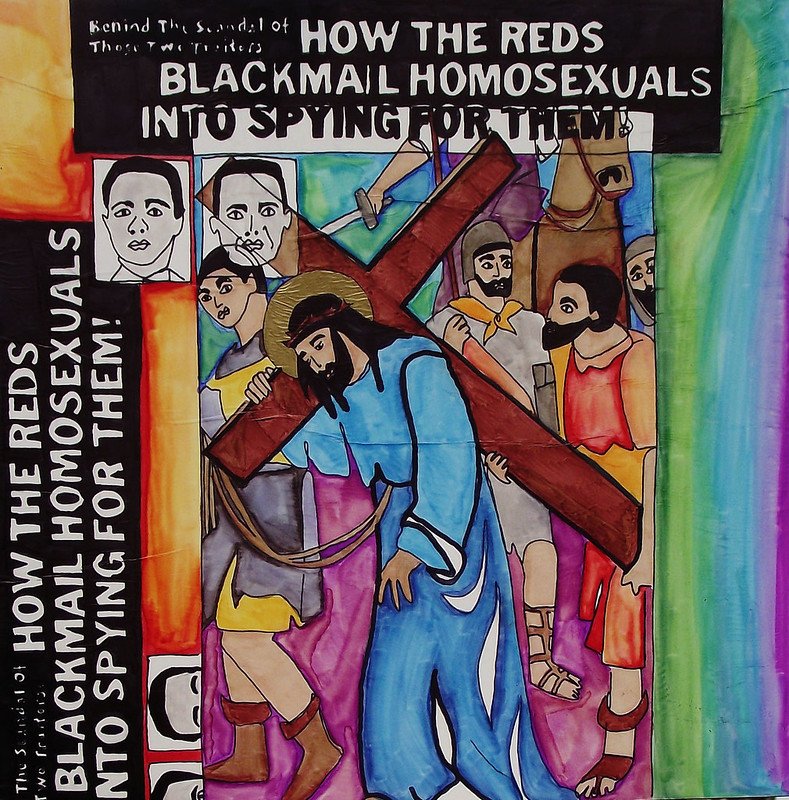

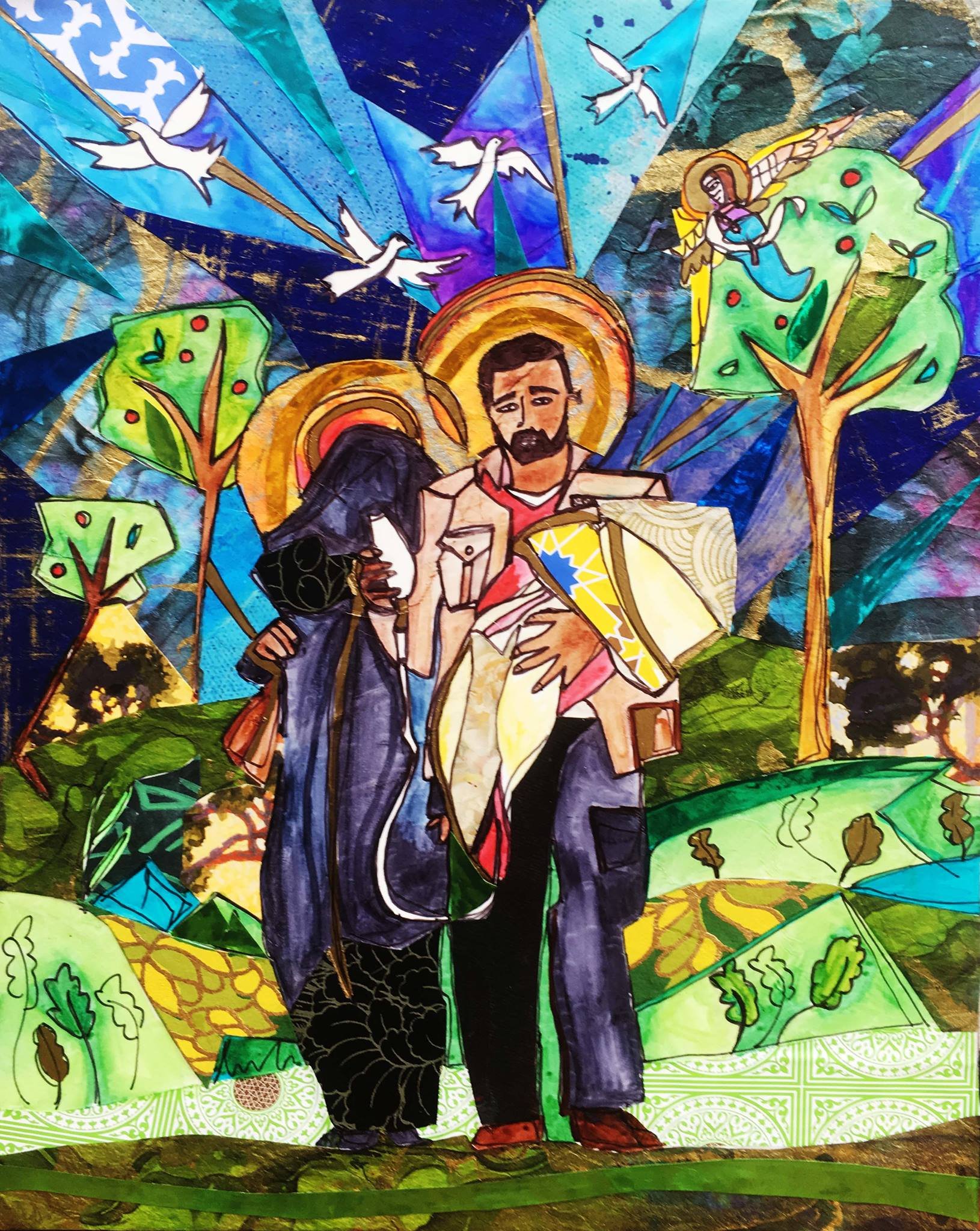

Jesus Accepts His Cross: The Seasons and the Symptoms of Mental Illness

The birds were as a transformation of trunk and branch and twig into

the elation which is the energy’s celebration and consummation! -Delmore Schwartz, May’s Truth and May’s Falsehood

Hospitalizations for mania occur most frequently in the summer, while hospitalizations for depression happen most often in the winter months.

I speak from my own experience and truth. My story is mine alone, and it is not the purpose of this series of work to project onto anyone else this story. I have experienced wide ranging degrees of mania and depression. and infinite feelings in between. So have, I imagine, most of you. The needs of Americans struggling to find quality behavioral health care are difficult to meet because our health care system operates from a "one size fits all" mentality. Holistic wellness does not fit into one standardized cookie cutter shape system or treatment.

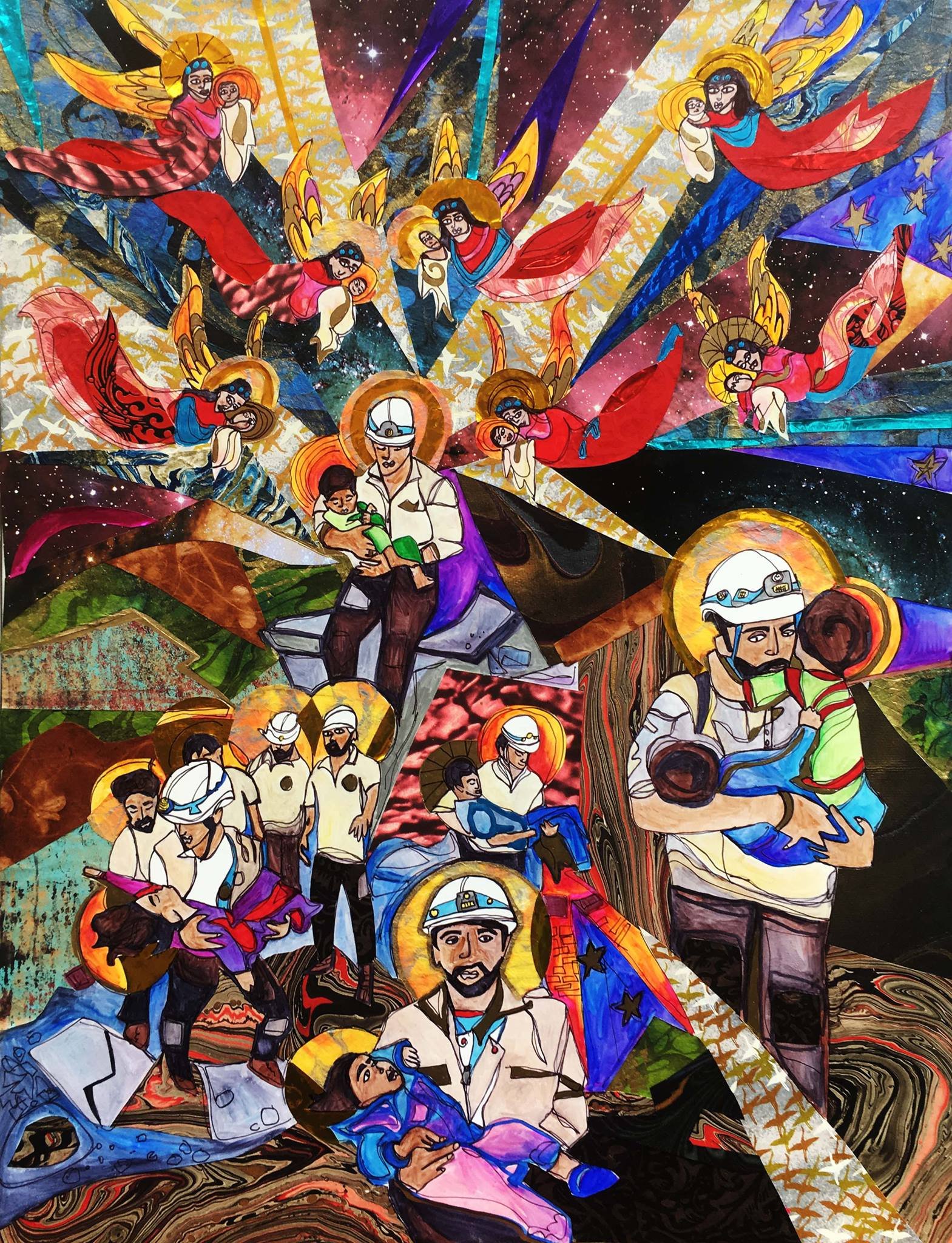

The artwork in this series begins in an attempt to express some of the experiential quality of mania. As the colors darken, l hope to illuminate the darkness of depression as well as some of the implications for social justice presented by American society's mistreatment of those with mental illnesses. The narrative shape of the series comes from Kay Redfield Jamison’s magisterial book Touched With Fire: Manic Depressive Illness and the Artistic Temperament. It's this book that shepherded me through the first year after my diagnosis. It helped me to understand the central point of this new series of work: people with mental illness experience the world in ways that illuminate great truths about the very nature of the human experience.

Jesus Falls for the First Time: The Creativity of Mania

"The kingfisher, he claimed, had evolved the brightly colored, scale-like feathers on its neck and wings by spending many hours sitting and staring down into the water at its prey – the fishes. The mackerel’s moire back reflected wave motions in the water, to the extent that one could copy and present them as waves on a canvas." - Olof Lagencrantz on the mind of August Strindberg

The stations illustrate the words of the artists profiled in Jamison's study of creativity and bipolarity, as well as some mentioned in another of her excellent books, Night Falls Fast: Understanding Suicide. Robert Lowell, Delmore Schwartz, August Strindberg, A. Alvarez, and Virginia Woolf are just a few of the artists included in this series. Many of their life stories have sad endings; they lived lives on the tightrope between the electric genius of just a little madness and the shattering horror of too much. The legacy left to us by these immortal empaths is their writing. We have their words, their stories of great joy and deep sadness. It's from these words that we know that the experiences of those with mental illness are deeply human and, in that way, a part of all human experience.

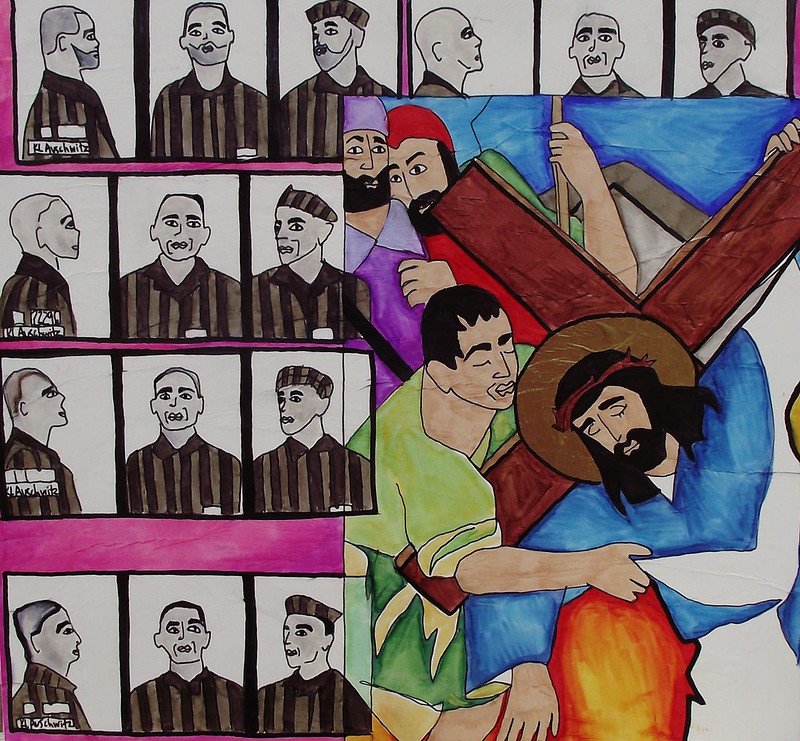

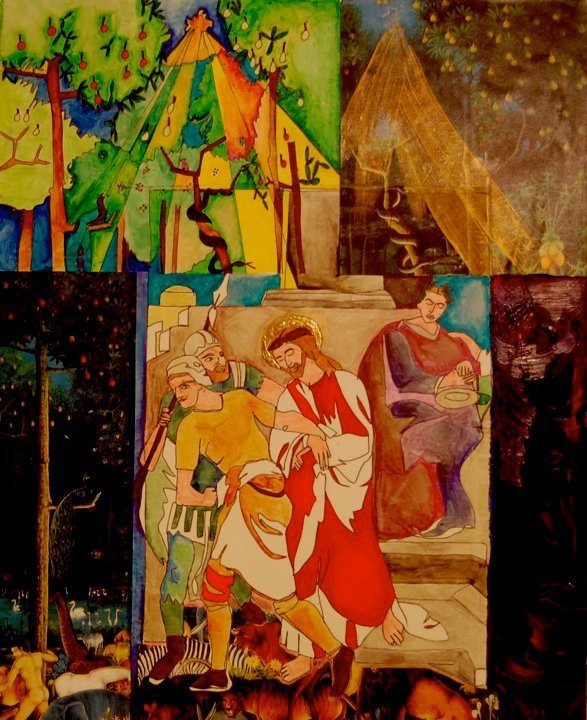

Jesus Meets His Mother: Depression

"A suicidal depression is a kind of spiritual winter, frozen, sterile, unmoving." - A. Alvarez

Nearly 3% of Americans -- 19 million people – suffer from some form of chronic depression. Of those, some 2 million are children. Bipolar disorder affects more than 2.3 million Americans and is the second leading cause of death of young women, the third of young men. As many as 10% of Americans can expect to experience a major depressive episode, that is, a period of depression lasting several months, within their lifetime.

As a Christian, the story of Jesus Christ is at the heart of my understanding of what it means to be human, so it makes sense to put his story into conversation with mine, with Virginia Woolf's and with the one million people who commit suicide every year. The church has a special moral obligation to educate itself on the social realities of people living with mental illness. I say "special obligation" because I believe that, too often, it is the church that most contributes to a society that devalues the Uves, experiences, and wisdom of people with mental illness. For me, the most terrifying aspect of my depression is the feeling of separation from Christ that it leaves in its wake. When l feel this way, going to church only makes the feeling of separation that much more painful. I worry that my depression is an offense to God, that my inability to pull myself out of my pity means that God hates me. I open my mouth to sing hymns of praise and the words turn to ash in my mouth. This isn't to say that churches should never sing praise hymns, that caring for those of us who live with chronic mental illness means to dwell in the darkness. Rather, we should live out the Scriptural understanding that there is time enough under heaven to tear and to mend.